In this blog post, I outline some key -isms and -ologies that often arise when teaching the philosophy of the social sciences. Students often find it difficult to grapple with this complex of approaches. Here I suggest ways of simplifying these issues for students.

<<<HOMEPAGE ||

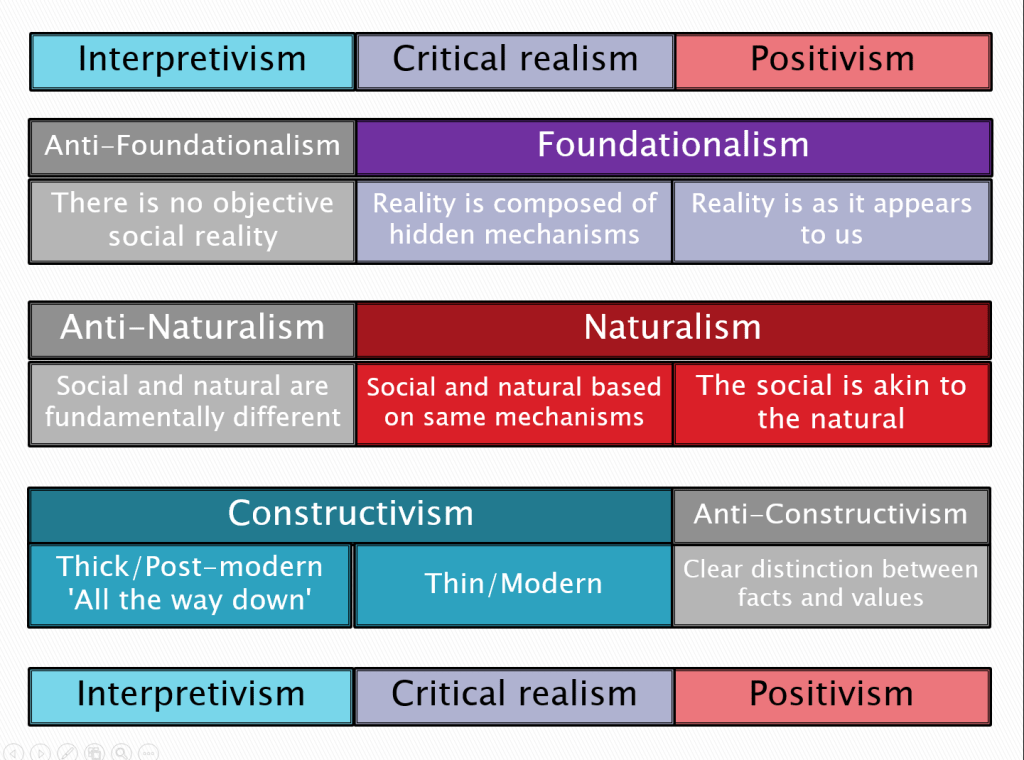

I have some new research in the pipeline, but in the meantime, I’ve been reflecting on this year’s teaching. In this post, I’m going to focus on a diagram that I’ve developed for teaching, which was designed to introduce post-graduate politics students (PhDs and MScs) to ontology and epistemology . The diagram builds on the increasingly common trend in political science textbooks whereby the approaches to political science are split into three main groups, each with their own distinctive ontological and epistemological assumptions. This trend, along with my own diagram, are innevitably simplifications, but learning must begin with simplifications so that there is a structure through which we can begin to explore nuance.

Ontology-epistemology

Ontology is broadly the philosophy of being and existence (explained in an earlier blog). Epistemology is broadly the philosophy of knowledge (to be explored in a future blog). Every approach to political research (and indeed all other research) unnavoidably relies on ontological and epistemological assumptions. This much seems to be widely agreed upon. However, from here on in, the issues are all thorny and contested. For example, one of the most basic disagreements is about which of the two philosophies is really the foundation of social research. Do we have to have a theory about what exists (ontology) before it is possible to develop a theory about what we can know about it (epistemology)? OR… Do we have to have a theory of knowledge (epistemology) before we can start making claims about what we know/believe to exist (ontology)?

Perhaps more controversially, there are contestations about whether certain questions are epistemological questions or ontological questions. For example, Marsh and Furlong (2010) discuss the question of ‘foundationalism’, the question of whether there is an objective social world, as the basic question of ontology. However, Bates and Jenkins (2007) argue that this question and the terms of ‘foundationalism’ and ‘anti-foundationalism’ are actually epistemological. Another example might be the debate over the fact-value distinction, with postivist researchers relying on the assumption that facts and values can be distinguished, and constructivist approaches tending to reject such a distinction. On the face of it, this is an epistemological debate about the nature of truth and the possibility of objective knowledge. However, it is also ontological because it raises a question about whether facts and values are separate elements of social reality.

Three Controversies and Three Foundations

These complexities stand in the way of the clarity needed to introduce the debate to students. Therefore, perhaps the best approach to the teaching of these subjects is to start by introducing the controversies themselves, and only come to the notions of ‘ontology’ and ‘epistemology’ slightly later. With this in mind, I have developed DIAGRAM 1, which shows three crucial controversies and three approaches that each take up a position within those controversies…

Therefore, the question of ‘foundationalism‘ is both epistemological and ontological, and it is of crucial importance for delineating approaches to political science (and indeed all social analysis). The question of foundationalism is the question of whether there is an objective social reality. In other words, can we imagine a birds-eye perspective on reality that is not the perspective of a particular subject but a perspective from which it is possible to comprehend every element of reality?

- A positivist response is to say ‘yes, the attainment of this perspective is the aim of science’.

- A critical realist response is to say ‘yes, we can imagine such a perspective and, although we can never actually attain it, our theories must assume its existence’.

- An interpretivist response is to say ‘no, every perspective is the perspective of a particular subject’.

Again, the question of ‘naturalism‘ is both ontological and epistemological. Ontology: to what extent are the social and natural worlds different. Epistemology: should we study the social and natural worlds in the same way?

- A positivist response is to say that the social world is fundamentally the same as the natural, and we should study it with broadly the same scientific approach.

- A critical realist response is to say that the social world and the natural world are different, but the differences are complicated and the two are not separate. Therefore, we need a unifying philosophy that incorporates both.

- An interpretivist response is to say that the social world is unique because it contains subjects. Subjects interpret and experience, subjects have the power to ‘act otherwise’, and subjects react to the theories we make about them

Constructivism is the claim that human thought is an artificial construct that is fundamentally intertwined with social relations. It is usually thought of as epistemological, because it is concerned with objectivity and the possibility of truth. However, it is also ontological because it is concerned with the link between ideas and institutions.

- A positivist response is to maintain a distinction between values and facts, arguing that the former may be socially constructed but the latter is not.

- A critical realist response is to accept that social construction means that our knowledge is fallible, but that we can use ‘judgemental rationality’ as a guide to objectivity (there is work to be done on this position!)

- An interpretivist response is to argue that all of our thoughts, beliefs, discourses, and ‘truths’ are social constructions, and that we must therefore abandon a search for objective/certain truth.

Conclusion

In summary, the boundaries of ontology and epistemology do not map clearly onto different philosophical controversies, as most philosophical controversies usually have an epistemological dimension and an ontological dimension. When introducing these ideas to students, it is best to start with the controversies themselves before introducing the concepts of ‘ontology’ and ‘epistemology’. In doing so, the three-way split between positivism, critical realism, and interpretivism is particularly useful.

<<<HOMEPAGE ||